Currently PhD Candidate at Bauhaus-Universität, Weimar/DE

Part of the research project "Plants_Intelligence. Learning Like a Plant", Institute Art Gender Nature IAGN, FHNW Academy of Art and Design, Basel/CH

https://vimeo.com/734817500

landscapes, newly created lands, modern harbours and a merchant fleet carrying goods from far-away continents. Faust is the logistics-king of international free trade, with Mephisto as his chief-ideologue and henchman. Only a nameless traveller and a friendly old couple, Philemon and Baucis, appear as their adversaries, who quickly fall prey to the capitalist turnover.

In cross-referencing Faust with the on-going violent repression of indigenous land claims in Patagonia, we

look to the far-away and yet so near geographies of this faustian relation to nature, and plea for those who

resist, and who have resisted through history.

And what does all this have to do with us?

Faust, Mapuches, Santiago Maldonado and the occupied land

In cross-referencing Faust with the on-going violent repression of indigenous land claims in Patagonia, we look to the far-away and yet so near geographies of this faustian relation to nature, and plea for those who resist, and who have resisted through history. We ask: what does the death of those nameless travellers mean for us here and now, how can they be called and recalled by their names, and how could the laments for Philemon and Baucis be translated into a critique of an unlimited „accumulation by dispossession“? How could Faust, in his final incarnation as land-developer, be understood today, how can his success, his burning ambition, his blindness and subsequent death be re-interpreted in the light of the on-going ecocide and the death toll of the extractivist and neo-colonial frontier?

Text by Naomi Hennig

Bibliothek APP’N’CELL NOW, Kunsthalle Appenzell/CH, 2020

Bibliothek Photograph und Text (Inkjet-print, 40 x 60 cm and notebook on shelf,

10,5 x 29,7 cm, 28 pages), 2015-2019

Elisabeth Pletscher (1908 - 2003) was a laboratory assistant and an activist for women’s voting rights. She gave her first political speech about women’s voting rights in 1959 and she voted for first time in Trogen in 1990. Her photo albums and personal papers are today part of the Canton’s Archive. In one of the boxes with the sign “Lektüren” there are seven notebooks where Elisabeth wrote the name of all the books she read from 1927 to 2003, with a description about each of them.

Bibliothek is composed by two parts: a photograph and a booklet with a list I created with the names of all the books which Elisabeth mentioned, organised by year and decade.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

EAC, Montevideo/UY 2018

Publicación con el ensayo de Ana Sol Alderete:

Todas las cámaras se fabricaron para fotografiar la Plaza Roja

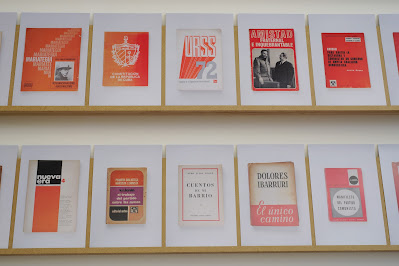

The variations of colours of the TV screen were transformed into

different red and magenta tones. Not green or blue, but red.

When we told them that the TV was not working well, they didn’t

agree; for them it was still perfectly functioning. This anecdote

gave the name to Life in Red, a long term project, which takes as

starting point the private and political life of my grandparents – both

convinced communists in Argentina, a country where Socialism

has never released as a system, but as utopia remained. An artistic

investigation into the history of Communism in the 20th century, the

use of personal documents to reflect on history and the change of

representation of images in different times and contexts.

Until now the project had several stages, which brought me to

different geographies and contexts. It arose from the need to

understand my own inheritance and the way my parents and

grandparents dealt with this history, in order to build my own

generational tools to act in the present.

Balada Tropical (Tropische Ballade)

Part of La vida en rojo. Installation, Inkjet-prints, 2019

In 1961 my grandmother traveled to Cuba as part of a delegation

of Argentinean workers. During the trip, she met Che Guevara,

visited cities and the country side. She didn’t take any photos, but

she wrote a letter to my grandfather Rafael, describing the paradise

she was seeing, the concretisation of the dream called revolution.

Balada tropical re-conceptualises and re-writes the trip of Isabel to

Cuba in 1961, taking as starting point her letter in relation with cuban

literature, my own research at the island and interviews with Cuban

women who are part of the so called generation of grandkids of the

revolution.

What is left now of this socialist paradise that my grandmother once

visited? Was it a paradise back then? Why is the representation of the

revolution mainly male? Why are female figures who where part of the

guerrilla, like Haydeé Santamaria and Celia Sanchez, not part of the

official discurse? How would the revolution be if they would not have

passed away in the 80ties? What politics would be like, if it would be

built on the rules and affections by women and the so called new

genders?

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Centro Cultural Recoleta, sala C, Buenos Aires/AR 2016

Hasta ahora el proyecto contó con varias etapas, que me llevaron hacia diferentes geografías (Argentina, ex República Democrática Alemana, Ucrania), con la intención de investigar sus contextos actuales y hacer visibles las marcas que el sistema y doctrina socialista dejaron en ellos. La vida en rojo nace de la necesidad de entender mi herencia familiar, para cuestionarla y tomar de ella lo que me sirva para construir mis propias herramientas generacionales y accionar en el presente.

La muestra plantea una instalación donde por primera vez dialogan en un mismo espacio expositivo diferentes obras del proyecto La vida en rojo. Una proyección de diapositivas sincronizadas de 1973 y 2008/2014 de la ex RDA (El viaje de Rafael); una crónica de viaje a Salashi, actual Ucrania; un video que registra una conversación con tres preguntas en el living de mis abuelos (La felicidad); y un ensayo de video (La vida en rojo) que funciona como espejo de las demás piezas expuestas.

Julia Mensch, Buenos Aires, junio 2016

Publicación Caлaшi-Salashi

Publicación Caлaшi-SalashiAdquirir en:

En Buenos Aires en Big Sur y Asunto Impreso

y en Berlín en Motto: http://www.mottodistribution.com/shop/calashi-salashi.html

Editado por Kosice European Capital of Culture

Segunda edición: Castellano o inglés

Tapa dura, 135 páginas, impresión offset blanco y negro, 17.6 x 25 cm

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Maisons Daura, Open Studio, Saint-Cirq Lapopie/FR 2016

In Conrad’s novel, the global link between colonia and metropolis, so central to the ideology of imperialism, is articulated by the emblematic last words of Kurtz: “The Horror, the Horror”. Back in Europe Marlow meets Kurtz’s fiancée, who asks him to repeat Kurtz’s final words before his death, to what Marlow lies and tells her that they were her name. In The location of Culture, Homi Bhabha takes Marlow’s answer as a poetics of translation, which locates the border between colony and metropolis. “In taking the name of a woman – the Intended – to mask the demonic ‘being’ of colonialism, Marrow turns the brooding geography of political disaster – the heart of darkness – into a melancholic memorial to romantic love and historic memory. Between the silent truth of Africa and the salient lie to the metropolitan woman, Marlow returns to his initiating insight: the experience of colonialism is the problem of living in the ‘midst of the incomprehensible’.“ 1

During the last years an unprecedented number of people from Middle Eastern and African countries–many of them fleeing war, persecution and extreme poverty–have been crossing borders into and within Europe, traversing the Mediterranean, the Balkans, and the English Channel. The images of dead bodies at sea, of refugees on overloaded, rickety boats, and of families climbing practically through border fences made of barbed wire have become iconic in our collective imagination. 2 “The Horror” has entered Europe, it has brought to the heart pf the European Union the incomprehensible, what is supposed to be outside of the Schengen Border, but of what the EU is also part of, and responsable of.

After 1492 in the today called Latin America, natives were enchanted by mirrors from the colonists. Today the Occident contemplates itself in a broken mirror of its new global unconscious, characterised by the increase of migrant workers and refugees and their not anymore definable national identities. 3 A mirror which reflects a past of colonisation by many of the European Nations, today part of the EU; a present in which companies are taking advantages in the so called “developing countries”; and a recent active participation in the wars in the Middle East. All this in contrast with the initiatives by citizens, who start to organise themselves to help at least a small amount of the thousands of refugees who enter the EU with no more than hope to survive and to have a little better life.

The experience of living in the “midst of the incomprehensible” is no longer outside of the Schengen Border, consequences are so much everywhere out there in the world, that it is not possible anymore to translate the far away horror into a story to tell in the civilised Occident.

Is it possible to re-write global history, taking into consideration the responsibilities which Europe has? Is it possible to continue closing borders to protect security and welfare states based on the suffering of other nations? Is it possible to continue playing, that the broken mirror is actually not broken?

The shape of the broken mirror can be used to reflect multiples angels, geographies and backgrounds, and to build new readings of the history and present, and strategies (artistic and not) to act and try to change it.

1 Homi K. Bhabha, El lugar de la cultura (The location of Culture), Ediciones Manantial, Buenos Aires, 2002

2 Mayanthi Fernando and Cristiana Giordano, Introduction: Refugees and the Crisis of Europe, https://culanth.org/fieldsights/900-introduction-refugees-and-the-crisis-of-europe

3 Fredric Jameson, Modernism and Imperialism, in Nationalism, Colonialism, and Literature, University Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2001

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------